Here’s a workshop activity that I have been using recently that seems to go down well with students and their teachers.

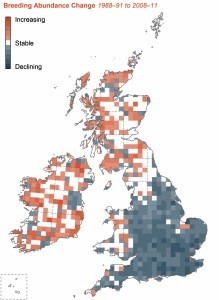

As learners enter the room, they find this image waiting for them with the instruction: What’s going on here…what questions are you asking yourself?

I then harvest comments:

- Some numbers are going up…some are staying the same…some are going down…

- Is it to do with the breeding of a particular creature?

- England seems to be doing worse than Wales, Ireland and Scotland

- It seems to be shifting north and west

- Why are numbers increasing around The Wash?

- Are the decreases in Ireland around Dublin and Cork?

- What kind of a creature could this be?

I introduce this image without comment:

I say: What do you know…what do you need to know?

- OK so it’s a bird…what kind of a bird is it?

- Why are its breeding numbers going down in some areas and not in others?

- What’s it perched on?

- What’s in its beak?

- What kind of habitat does it like?

- What does it feed on?

- Is it here all the time or is it a migrant?

I then drop this article by Michael McCarthy on the table and say – This might help – one member of your team skim read – use a highlighter – and see if there’s any useful data here…

On the loch below us, where one morning an otter swam lazily past the cottage window, causing the children to choke on their scrambled eggs in the scramble to see it, eiders are displaying, the archetypal ducks of the North. The fat males are fabulous, striking studies in black and white, but they also have a stunning salmon-pink flush on their breasts, and they compete to show this off to the dowdy brown females by throwing their heads back and raising their bodies out of the water. Each time they do this they make a curious sound which is sometimes described as ah-oo, ah-oo, but listening to it drift across the loch it seemed to me more like a small engine being revved: not quite varoom, varoom, more vareem, vareem.

But it is another sound which has made the deepest impression on me, diminutive though it is. It is a silvery falling cadence, heard almost everywhere, heard now at this moment, even as I am writing this, from the birches which surround the cottage: it is the song of willow warblers. It is soft and it is sweet and if you walk over the hills it is coming from every isolated birch clump, adding a surprise touch of softness to the northern landscape’s severity.

I find it captivating and I suppose that’s partly because I know where it comes from: tropical Africa. The eiders have been in this part of the world all year, more or less, as have the ravens croaking on the ridge, and the oystercatchers whistling on the beach, and the gannet which saunters into the loch each morning from the open sea and breezes around looking for fish worth catching. But these matchbox-sized bundles of feathers were a month ago in Senegal, and The Gambia, and Guinea-Bissau; and they have just flown 3,000 miles over the Sahara, and the Mediterranean, and the Pyrenees, and the Channel, and the length of Britain, to get to the Isle of Skye and start singing.

We have known this for less than a century. It is a hundred years next month since the Staffordshire solicitor John Masefield, an enthusiast for the new-fangled practice of bird-ringing, ringed a swallow chick in his porch which 18 months later, turned up in Natal, South Africa, and thus revealed the scarcely-believable scale of bird migration. It is a scale incredible by numbers as well as by geography. About five billion birds are thought to fly north out of Africa every spring, to breed across Eurasia before returning south for the winter, and of these the willow warbler is one of the most numerous of all, with perhaps in excess of 100m birds making the journey, of which about four million are thought to come to Britain.

Yet in England willow warbler numbers are steadily dropping, and are down by a third since 1995. Nobody knows why; nor does anyone know why, curiously, the numbers in Scotland are definitely increasing, up by perhaps a fifth over the same period (it may be that the English birds and the Scottish birds migrate to different parts of West Africa with conditions varyingly favourable in different regions.)

So if you want to hear the tiny symphony which is willow warbler song in spring, an Easter visit to Scotland is as good a way as any. Never mind the red deer stags, and the golden eagles, and the otters in the sea lochs, not to mention the mountains and all the rest of the magnificence – come to Skye for the willow warblers.

And then I say: What do you know…what do you need to know? To which they respond:

- This is a willow warbler

- It comes to these islands from west Africa to breed each spring

- Its habitat is changing

- Its breeding numbers are falling

- Its having to move farther north and west to breed

- Is this to do with climate change?

- Is there anything that can be done…is being done to stop this from happening?

And now the questions to stimulate enquiry-mindedness: what might you investigate to get to the bottom of this situation…what hypotheses are you generating?

The following is a sample of the ideas that have been generated recently by students – not provided by myself as the teacher:

- Look into the breeding cycle of the bird

- Research its habitat and see if this is being destroyed

- Find out about what it feeds on and whether this is changing

- Explore climate changes in the UK during the last twenty years

- Find out more about the area around The Wash

- Compare climate and habitat in Scotland, Wales and Ireland with England

- Research the impact of urbanization and pollution on wildlife

And this – to me – is real science; where students are stimulated to ask questions and eager to come up with their own answers and solutions because their teacher provides enough to stimulate curiosity but withholds plenty so that real learners can make the links and connections for themselves – capitalising on what they know already, backing their hunches and using the plethora of information that’s out there with discernment and discrimination.

You might like to define recipe science for yourself.

Comments are closed.