I have spent much of the past few weeks considering the issues that have faced Scottish schools for over a decade as a result of the Donaldson Report. This report spawned their Curriculum for Excellence which is built around four key purposes, sometimes referred to as key capacities. These purposes look to the longer term student-based outcomes of the curriculum; that “all children and every young person should be successful learners, confident individuals, responsible citizens and effective contributors to society and at work.” Each of the purposes is described more fully, so for example

“Successful Learners are:

- enthusiastic and motivated about learning

- determined to reach high standards of achievement

- open to new thinking and ideas

and they can:

- use literacy, communication and numeracy skills

- use technology for learning

- think creatively and independently

- learn independently and as part of a group

- make reasoned evaluations

- link and apply different kinds of learning”

Such descriptions offer an interesting blend of important learning behaviours, like enthusiasm and motivation, creativity and independence, and other more skill-based outcomes like literacy and numeracy.

Every teacher I talk to in Scotland tells a similar story – they are enthusiastic about the CfE and like the idea of creating successful, confident, responsible and effective learners. After all, what’s not to like? But the problem is that teachers know that many of their students aren’t like this, and worse, they suspect they’re not becoming more successful, confident, responsible or effective over time. So teachers like the intention, but have little idea of how to help make it happen over time.

The development of a set of valuable learning habits, that are seen as essential for learning, life, work and citizenship, has implications not only for what is taught and learned but, more importantly, how it is taught and learned. Although schools and teachers are keen to help realise CfE’s four purposes, they seek greater clarity on the practical implications of balancing these higher purposes of educating young people, and the more obvious business of curriculum areas and standards. They inevitably ask:

- What do we need to do differently to fulfil these purposes?

- How do we create a blend of the ‘what’ with a more expansive ‘how’ of the curriculum?

- Is it possible to do this in the time available and still improve standards?

- How will we know whether any changes we make are successful?

How is it possible to balance these two aspects of education, to have them work synergistically not competitively, in concert rather than in conflict?

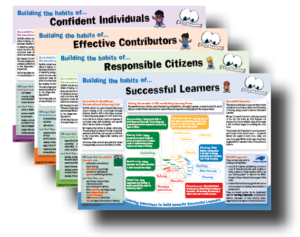

Building Learning Power answers all these questions. It aims to put the ‘how’ of learning at the heart of education, and help learners to grow their learning behaviours. As a result of our work with Scottish schools, we have produced four ‘At a Glance’ cards to show how Building Learning Power can interface with the Curriculum for Excellence, sketching out a practical, learning-centred approach to keeping the curriculum in balance while fulfilling the CfE promise. The ‘cards’ are freely available in a dedicated section of our website which explores these issues further.

Curriculum for Excellence: fulfilling its promise

Curriculum for Excellence: fulfilling its promise

This online resource sketches the what, why and how of developing the sort of powerful learners envisaged in Scotland’s Curriculum for Excellence.

view CfE resource… onwards to wales

The curriculum in Wales has also been under review, again by Graham Donaldson. His recent report, Successful Futures, proposes a similar but more complicated set of four outcome-focused purposes:

‘that children and young people develop as:

- ambitious, capable learners, ready to learn throughout their lives;

- enterprising, creative contributors, ready to play a full part in life and work;

- ethical, informed citizens of Wales and the world;

- healthy, confident individuals, ready to lead fulfilling lives as valued members of society.”

And as with the Scottish curriculum the purposes are further described. So, Ambitious, capable learners:

- “set themselves high standards and seek and enjoy challenge

- build up a body of knowledge and have the skills to connect and apply that knowledge in different contexts

- are questioning and enjoy solving problems

- can communicate effectively in different forms and settings, using both Welsh and English

- can explain the ideas and concepts they are learning about

- can use number effectively in different contexts

- understand how to interpret data and apply mathematical concepts

- use digital technologies creatively to communicate, find and analyse information

- undertake research and evaluate critically what they find

and are ready to learn throughout their lives”

Here again we see another blend of important learning behaviours, punctuated by some skill-based outcomes. And again we detect a similar reaction by teachers as they gear up to start the new curriculum in Sept 2018: broad agreement with the curriculum purposes, but uncertainty as to how to achieve them. There is concern that despite a brief nod to the use of four wider skills:

- critical thinking and problem solving;

- planning and organising;

- creativity and innovation;

- personal effectiveness

and a set of twelve pedagogy statements, there’s little or no indication as to how the purposes might be reached. Watch out for a similar set of ‘At A Glance’ cards and online starter ideas for Wales, early in the new year.

And then there’s England

Do England’s students not need to be successful, ambitious, confident, creative, responsible and so forth? There are no such purposes driving their new curriculum.

There was a valiant previous attempt to bring learning behaviours into focus in England’s schools through the Personal Thinking and Learning Skills (PLTS) aspect in an earlier ‘new curriculum’ for secondary schools in 2008. Some would say these too were doomed because the 6 areas (independent enquirers, creative thinkers, reflective learners, team workers, self managers and effective participants – remember them??) were ill-defined and lacked a supportive framework with which schools could work.

Since then, the 2014 update to the National Curriculum still has echoes of producing successful learners, etc., but unlike Scotland or Wales it is not a core purpose for the curriculum. And the balance seems firmly on the side of the ‘what’ rather than the ‘how’, with these two aspects of education working competitively not synergistically, in conflict rather than in concert.

As Donaldson observes in Successful Futures:

“England retains subjects as the main curriculum building blocks. The national curriculum remains structured around 12 subjects, split into core and foundation, with associated programmes of study. Recommendations from independent reviews to move to a structure based on capacities and areas of learning have been rejected by the government.” (page 37, Successful Futures)

Nonetheless, the (English) National Curriculum has its own aims, quite unlike those in Scotland and Wales. The 2014 Statutory Guidance explains the aims thus:

“The national curriculum provides pupils with an introduction to the essential knowledge they need to be educated citizens. It introduces pupils to the best that has been thought and said, and helps engender an appreciation of human creativity and achievement.” (Section 3.1).

[Whether this is an aim or not, I will leave you to decide!]But – Which of these National Curriculums offers the more inspiring vision for the future of education, I wonder?

Hi Graham.

Once again a thought-provoking and reflective blog entry. I certainly agree that the vision and aims of the new curriculum being implemented in Wales are refreshing and inspiring – wishing England would now ‘see the light’ and follow suit. In my experience working with and training teachers from a wide variety of schools in Wales, I find it a shame that many of the developments of the new curriculum don’t appear to be asking ‘why?’ often enough and critically evaluating curriculum content in order to reduce the vast amount of content currently on the curriculum. If this could be done more thoroughly, along with a greater focus on ‘how’ schools and teachers are approaching learning, we would see more powerful and meaningful change, rather than a ‘repackaging’ of content.

Now, if only there was a program that could help schools do that….