For some years now many primary schools have been consciously working on the development of their students’ habits or dispositions of learning…those attributes of character that make you more or less likely to: persevere and learn well with others; check out and change your learning as you go along; think carefully and question things critically. These ‘hows’ of being a successful learner seem to be easier to integrate into primary than secondary schools. Furthermore research now firmly shows that these learning habits have strong effects on educational attainment and additional positive effects on life outcomes beyond school. So, what is it that stops secondary schools taking up this challenge and especially so with the emergence of the new Ofsted framework? Why is it so difficult to infuse the development of learning habits into the secondary curriculum?

There may be a number of factors at work:

- Primary schools have always focused on the development of the whole child and feel less driven by attainment alone.

- In an ideal world, secondary schools would be taking forward the work of their contributing primaries, adding to students’ abilities and tendencies, but many find this difficult as we will discover below.

- Some secondary schools have to undo negative views of learning in their students – for example that learning is done for them not by them – before they can begin to focus on developing the required learning behaviours.

But these factors are eclipsed by the differing organisational features of primary and secondary schools.

Here’s an activity that illustrates this difference – try it on for size.

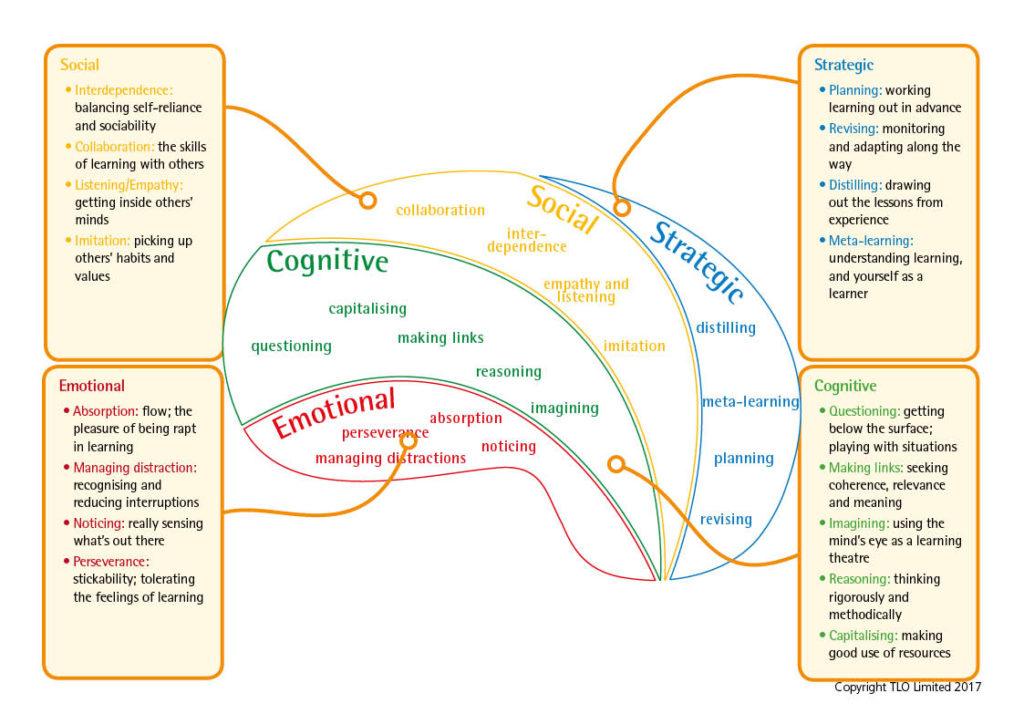

Here is is a diagram of the Supple Learning Mind. Take a look at the Emotional domain – (in red) the dispositions of Absorption, Managing Distractions, Noticing and Perseverance.

Can you name some of your students who: enjoy a challenge; get ‘lost’ in learning; can regain focus after being distracted; are attentive to detail, and so forth. What about your students who don’t exhibit these characteristics? Can you name any and are these students easier to name?

When we try this activity on our courses, the difference between primary teachers and most secondary teachers is marked. Primary teachers start to name students in both lists. They discuss whether they are tending to focus on just one or two students or whether they are naming many students across the ability range, whether their lists have a gender bias, and they consider where their high achievers and under-achievers are appearing. This rich conversation continues for the other 3 domains of learning (cognitive, social and strategic). This morphs into a fascinating chicken and egg conversation: are students on the ‘do not’ list there because they are low attainers, or are they low attainers because they are on the ‘do not’ list? It is the beginnings of a realisation that improving learning behaviours is a central part of the standards agenda, rather than an alternative to it.

Secondary teachers, on the other hand, look at us as if we have set them a near impossible task. Was it like that for you? Did you struggle, as many do, to go beyond naming a couple of exceptional learners in each list? Experience tells us this is because secondary teachers don’t have the time to get to know their students as learners. This is hardly surprising – with over 200 students to interact with weekly, they do well to know their students as Mathematicians, Linguists, Historians etc, let alone knowing their individual learning strengths and weaknesses.

Quite simply, the teacher working predominantly with the same students all week is better placed to understand and nourish student learning behaviours. No surprise there.

And once the learning dispositions have been identified in students, the question of how to build them throws up the same issues. Think about a group of students with a tendency to give up at the first sign of difficulty and who have become dependent on their teachers giving ready answers. A primary school teacher faced with such a group could plan to use a range of strategies, over perhaps a couple of months, to build their students’ inclination to face up to challenge with confidence. Contrast this with the sheer complexity of achieving the same across a cohort of 250 secondary school students, taught by upwards of 40 teachers.

The scale of secondary schools, combined with the relatively short time individual teachers spend with particular students, make the task of building Learning Power in secondary schools more difficult.

In a series of blogs over the next few weeks, we’ll explore how some secondary schools have decided to introduce students to their Learning Power and develop this across the curriculum, and take a look at the pros and cons of these various approaches.

By Steve Watson – Principal Consultant

Steve Watson works as Principal Consultant for TLO. He is former Deputy Headteacher of Alderbrook School (Secondary) and co-owner of The Learning Nursery pre-school. Steve’s commitment to radically challenging teaching and learning in a comprehensive school context has made him focus schools on the development of their own language for learning based on Building Learning Power. His strategic yet hands-on approach wins respect and ensures that the vision is realised in practice.

Steve Watson works as Principal Consultant for TLO. He is former Deputy Headteacher of Alderbrook School (Secondary) and co-owner of The Learning Nursery pre-school. Steve’s commitment to radically challenging teaching and learning in a comprehensive school context has made him focus schools on the development of their own language for learning based on Building Learning Power. His strategic yet hands-on approach wins respect and ensures that the vision is realised in practice.

No comments yet.