How is building learning power different? What’s the distinction between learning more, learning better and becoming a better learner?

2. From there to here

An enthusiasm for ‘better learning’ has motivated teachers for a long time. In attempts to help students learn more or learn better, teachers tried to understand learning styles, multiple intelligences, and the like. In attempts to help students improve their organisation of knowledge or the effectiveness of their memory, teachers used tools like mind maps, mnemonics, and other study skills. These approaches have laid the ground for a deeper, more permanent set of approaches, whose aim is to get beyond learning more, or learning better, to helping students to help themselves become better learners.

” I can’t think of anything more worth learning than learning to learn. It’s like having money in the bank at compound interest” David Perkins. Project Zero, Harvard University

Key issues

- learning is a learnable craft

- learning how to learn involves attitudes, values, interests and beliefs

- developing better learners is done with and by learners rather than to learners

- involves cultivating dispositions and values rather than training skills

- is not an inevitable by-product of ‘traditional effective teaching’.

- is about making students ready and willing as well as able to learn

2a We used to think…

that ‘improving the quality of students’ learning’ was really about ‘raising attainment’. Learning was seen as a performance rather than a process (learning more). Later ‘learning to learn’ aimed to develop ‘study skills’. ‘Good teaching’ was still content focused, plus delivering study skills (learning better). Then we moved to the idea of removing stress levels to raise performance levels, but the focus was on how the teacher could ‘teach’ better, rather than on how students could be helped to become better learners.

2b But now we think…

… of ‘learning’ as an interesting process going on in children’s brains. When we all believed that ‘intelligence’ was fixed at birth there seemed little point in trying to cultivate it. Now we know just how learnable learning is we are realising that there’s a place for developing how we learn. Research uncovered some dimensions or energies or powers that can be used to shape how we learn. They could shape, for example, the growth of our resilience in learning, our learning relationships, our thinking skills and how we manage our learning. Ask yourself;

- What does resilience mean to a four-year-old, or ten-year-old, or a sixteen year old and how can it be appropriately stretched?

- What kinds of thinking skills will help students become better learners?

2c Disposition; the hidden dimension of learning

What if some of the girls in your class believed that ‘Maths isn’t for girls’ or that some students thought that ‘If you can’t solve it in a minute, you can’t solve it at all’ or that ‘Bright people never have to try’. All these erroneous ideas cause students to be disposed to give up easily, to feel stupid, to feel disengaged. Think of ‘dispositions’ as indicators of the degree to which one is disposed to make use of a skill or knowledge.

Underlying this approach is a recognition that learning how to learn involves more than skills, it involves students attitudes, values, interests and beliefs as well. It’s about helping students to help themselves to be disposed to persist, to question and be curious, to collaborate harmoniously and to be open to new ideas.

The good thing is that these dispositions, inherent in all of us, are not fixed at birth. They can be developed by all of us regardless of ‘ability’, social background or age. Extending our learning power has no limits.

‘Dispositions to learning should be key performance indicators of the outcomes of schooling. Many teachers believe that, if achievement is enhanced, there is a ripple effect to these dispositions. However, such a belief is not defensible. Such dispositions need planned interventions.’

John Hattie, Visible Learning

2d Where do you stand?

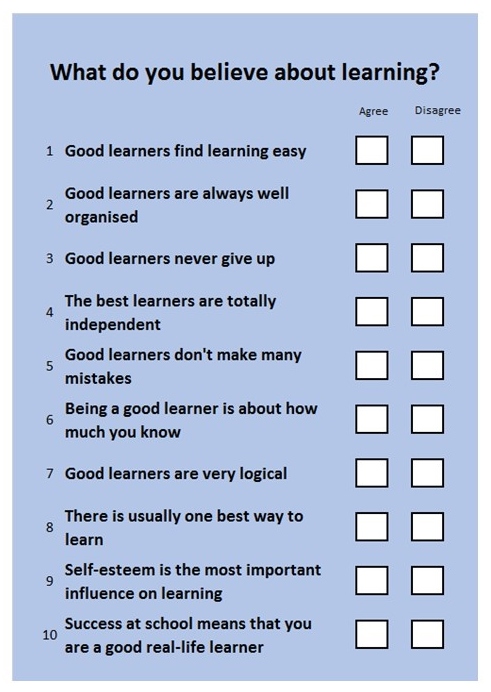

Think about what you think good learners do. Mull over the statements and indicate whether you broadly agree or disagree with them.

Think about how you teach in relation to each of them. To what extent does your teaching embody what you say about good learning?

Do you sometimes act as if you believed something different from what you say you believe?

From learning more, to learning better, to becoming better learners

From learning more, to learning better, to becoming better learners

Learning more: an interest in raising achievement

- Outcome of schooling (e.g. KS2 SATs results)

- ‘Good teaching’ was about content and acquisition

- ‘Good teachers’ could put across information, develop literacy and numeracy, etc.

When schools’ prospectuses first started talking a lot about ‘improving the quality of students’ learning’ what they really meant was ‘raising attainment’. ‘Learning’ was only used to refer to the outcome of schooling, learning as performance rather than learning as a process. There was no recognition of ‘learning’ as an interesting process going on in children’s brains.

Learning better: developing study skills

- Hints and tips on retaining and recalling for tests

- Practising techniques

- ‘Good teaching’ was still content focused, plus delivering study skill based on practical things that students could do to improve the organisation of their knowledge, their memories, or the effectiveness of their revision. The concern with ‘improving learning’ was linked to exams with numerous hints and tips on how best to retain and recall what had been learned.

Learning better: styles and self-esteem

- Characteristic ways of learning (e.g. multiple intelligences)

- ‘Good teaching’ included reducing stress levels and helping students raise their attainment levels

- Concern shifts to the ‘how’ of teaching

The concern with the emotional aspects of learning led to a tsunami of approaches but lacked an overall framework. Mind maps to help organise and retrieve knowledge; bottled water to lubricate students’ brain cells to ensure they didn’t ‘dry up’; learning styles of overall learning strengths (auditory, visual, kinaesthetic) which people were encouraged to play to; background classical music; the centrality of bolstering students’ self-esteem. L2L manuals became fashionable but the focus was on how the teacher could ‘teach’ better, rather than on how students could be helped to become better learners.

Becoming better learners: involving students in their learning

- Concerned with how students can be helped to help themselves (e.g. think creatively)

- Teachers themselves involved in becoming better learners

- Developmental and cumulative — encouraging the ‘ready and willing’, not just the ‘able’

Why the shift in focus? A glance at the research

When we all believed that ‘intelligence’ was fixed at birth there seemed little point in trying to cultivate it. Now we know just how learnable learning is we are realising that there’s a place for developing how we learn. Research at Bristol University uncovered seven dimensions or energies or powers that can be used to shape how we learn. This was the beginning of shaping a good route map of how children’s learning power grows: a route map to do with the growth of our resilience in learning, our learning relationships, our thinking skills and how we manage our learning. The route map causes questions such as:

- What does resilience mean to a four-year-old, or ten-year-old, and how can it be appropriately stretched?

- What kinds of thinking skills will help students become better learners

Questions such as this explain why this ‘learning power’ approach is often referred to as ‘building’ learning power.

The secret of learning power: disposition to make use of skill

Underlying this approach is a recognition that learning how to learn involves more than skills. How, and how well, children learn can’t be reduced to a matter of ‘skill’; it involves their attitudes, values, interests and beliefs as well. For example…

Kamini believes that ‘Maths isn’t for girls’ so she is not predisposed to try hard tasks. Neither is Fred, but for a different reason: he believes that ‘If you can’t solve it in a minute, you can’t solve it at all’. Evie thinks that ‘Bright people never have to try’, so she feels stupid when she can’t do something easily, and gives up too.

Think of ‘dispositions’ as indicators of the degree to which one is disposed to make use of that skill or knowledge. Rather than nouns, ‘dispositions’ are adverbs — those little signifiers of ‘time, manner and place’ that modify the verbs they accompany.To be disposed to persist, for example, is simply

- to show persistence across a broad rather than a narrow range of occasions;

- to tend to persist in the face of more severe obstacles or frustrations; and

- to have a rich repertoire of ways of supporting and encouraging one’s own persistence.

To be disposed to ask questions is to

- tend to ask questions in English as well as in maths

- to ask questions despite a degree of discouragement or fear.

When one is ‘disposed’ to self-evaluation you

- stand back from time to time and ask yourself how it is going

- self-evaluation has become routine, second nature, and across the board.

This shift in terminology reflects the influence of a particular strand of research that has emphasised the difference between skills and dispositions. David Perkins of Harvard University and others have shown that people often appear less capable than they are, not because they don’t possess the skill they need, but because they don’t realise that now is the right moment to call that skill to mind and make use of it. They lack what Perkins calls ‘sensitivity to occasion’. Skills and techniques aren’t enough. Students must not only possess the requisite capabilities; they must be ready, willing and able to use them when the time is right.

We need to move from thinking about learning as a set of techniques and skills that can be ‘trained’, to a set of dispositions, interests and values that need to be ‘cultivated’.

Comments are closed.