Schools socialise their students into ways of thinking about learning: how to go about it, which kinds of learning are well thought of, how to think of themselves as learners, and what aspects are worth paying attention to. In all kinds of subtle (and not so subtle) ways, answers to these questions seep into your students’ minds and shape their attitudes towards learning.

This kind of learning culture in classrooms depends a good deal on the way teachers talk about learning. So this week we thought it might be useful to look at some quick wins that you can easily make in the language you use and recognise, with a specific focus on perseverance.

1. Work versus Learning

From: Work

In using the word ‘work‘ for example you may well be saying things like “Get on with your work” or “Have you finished your work” or ” Your Homework project is to…”

To: Learning

To substitute ‘learning’ for ‘work’ you could start saying “How is your learning coming along?” or “Is this piece of learning finished?” or “Where is your Home learning?”

Why bother?

Teachers have traditionally talked much more about ‘work’ than they have about ‘learning’. One study carried out in London schools in 2002 compared the frequency of use of these two words, and found that ‘work’ was used 98% of the time, and ‘learning’ only 2%.

There’s nothing wrong with the word ‘work’ but it doesn’t entice you to get interested in the activity itself. You will be pleasantly surprised at the effect on your students if you talk less about ‘work’ and more about the process of learning itself.

Making this little shift isn’t as easy as it sounds. Some years ago we worked with a teacher who found it really hard to stop using the word ‘work’ and her way to tackle that was to enlist the help of her students. She carried several five pence pieces and a small money box around with her. She placed the money on her desks in various rooms and asked her students to wave at her gently if and when they spotted her using the word ‘work’. This triggered her to put one of her 5 pence pieces into the little money box. This trick worked a treat. By the end of term she had shifted her habit of using ‘work’ to using ‘learning’, she had donated enough money to pay for a couple of new books for the school library and her students were intrigued to know more about learning and how it worked.

In another study two groups of volunteers were asked to rewrite the captions to Gary Larson cartoons (The Far Side) so as to change their meaning. For one group this activity was referred to as ‘play’ while for the other it was referred to as ‘work’. Not only did the ‘play’ group find the activity more pleasurable than the ‘work’ group, they also reported being much more locked on to it, their minds wandered much less, they were more imaginative, and they learned more from the activity.

Give yourself a challenge

First ask yourself…

- Do I have a tendency to use the word ‘work’?

- How long do I reckon it would take me to make the switch to using the word ‘learning’?

- What other words might I try to use instead of ‘work’… to play, explore, investigate, puzzle……….?

- If it proves difficult, what sort of help might I enlist?

And when you do make the switch…

- make a note of whether and how classrooms feel different.

2. Putting meaning into effort

From: Woolly nudges

‘Make more effort’ is a common teacher comment, but what does it mean to the student? What are they supposed to actually do? What sort of effort, for what purpose?

To: Practical nudges

Use and talk about practical tactics that students might use which would constitute ‘effort’. For example you might suggest they use success criteria to help direct their effort.

Why bother

‘Effort’ is one of those words that has a long association with schools and learning. It used to feature in school reports showing a grade for how much effort you had put in during the term or year. Some years ago I remember my youngest son coming home from school saying “They (his teachers) say I have to put in more effort. What does that mean?” Indeed what does it mean? What do teachers expect students to do other than perhaps put in more time, manage their distractions or just con-cen-trate. How can we make the word ‘effort’ mean more to students?

Effort: it’s about focusing and re-focusing the mind on the learning you are doing. Something is, or should be, directing students’ attention. But to be useful effort needs to be targeted, and with effective input from the teacher. Effort needs a direction and a purpose. We could make effort more purposeful and targeted simply by saying things such as “I think you might…” or “I see you have put in more effort by:

- using a different/new/ [specific] strategy

- using the trial and improvement method to deal with that challenge

- using the success criteria to direct what you are doing

- asking for feedback on how you could improve

- putting ideas on bits of paper to free up some space in your working memory.”

Or you could remind students of past effortful behaviours: “What did you do to do so well on that test? You read the material over several times. You underlined the key points. You picked out the hard parts and focused on those. You wrote summaries to help you remember. All that effort really worked.”

These and many similar positive commentaries will help students to realise what to do to ‘make more effort’.

But also...using learning power language helps teachers to be even more specific about what sort of effort they suggest students make. As one teacher put it;

‘I often used to just tell students to make more effort, and got blank stares back. But when I started using Building Learning Power language I realised I could be much more specific about “making more effort.” I could turn my prompts and nudges into really useful statements. So now I watch students carefully through the Building Learning Power lens and say things like “how could you use your imagination to…?”, Or, “what questions might be helpful to take you further with this?”. I’ve started defining the sort of effort I want them to make’

Give yourself a challenge

First ask yourself…

- Do I have a clear and consistent idea of what I mean by ‘effort’?

- What learning tactics do I frequently spell out and recognise as effortful to students?

- What other tactics might I add to my list of the tactics of ‘effort’?

- What do my colleagues use? Do they use a similar list?

- Would a whole school discussion on this topic be useful?

And when you start making effort more understandable and practical to students…

- make a note of whether and how your students react and if their learning improves.

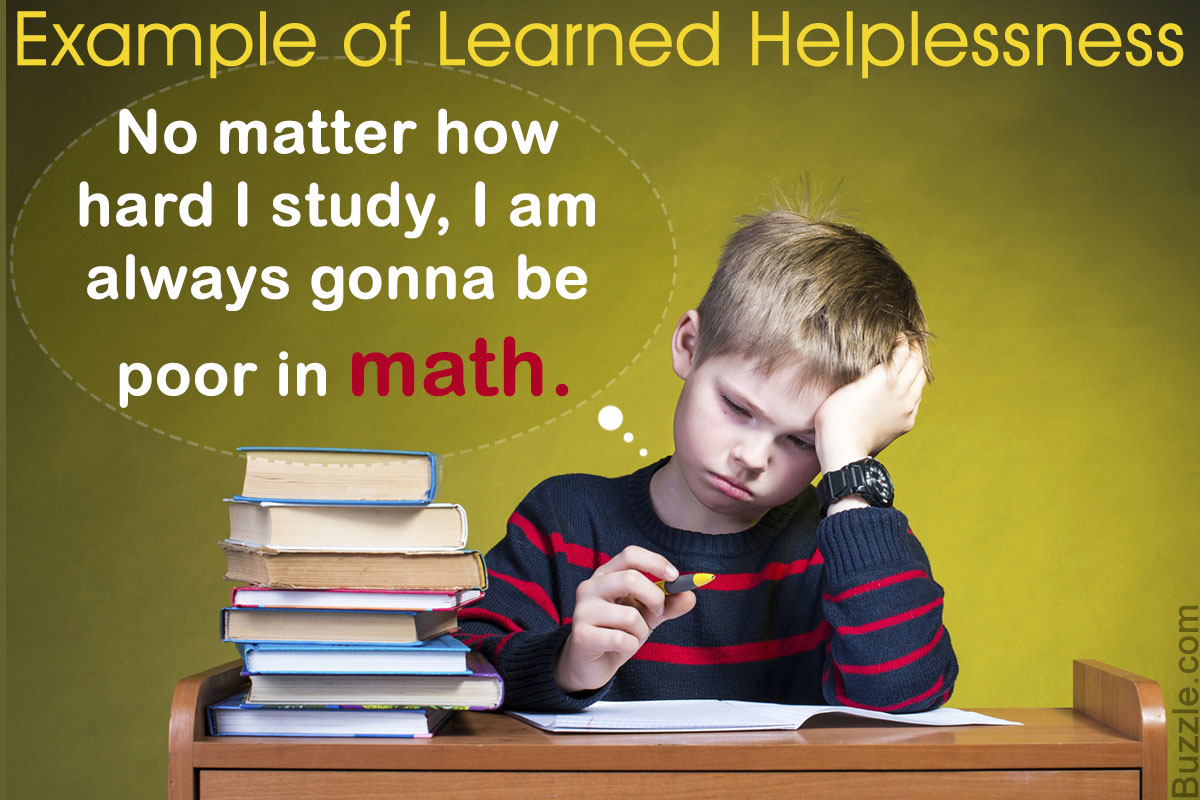

3. Pessimistic to optimistic student talk

From: Pessimistic student talk

Students often use phrases like “I never understand what my teacher is going on about”.

To: Optimistic student talk

How might you encourage more optimistic student self-talk such as “I am finding it hard to understand this today; maybe I should look back at what I did last time.”

Why bother?

As teachers of learning power you will be on the look out for how students perceive learning and help them to re-frame their ideas. Some words can be especially challenging. Words like ‘never’ and ‘always’ can give learners a damaging view of themselves. If a student says “I never understand what my teacher is going on about”, or “Maths is always too hard for me”, they suggest a pessimistic view of learning, one that is unlikely to cultivate the kind of persistence that more optimistic accounts might bring. Constant use of ‘never’ and ‘always’ suggests a lack of resilience, and, for the learner, can become something that seems permanent and unalterable. They have learned how to feel helpless.

If you come across this sort of negativity in your classroom(s) try suggesting small practical ways students can build up their resilience. For example:

- If students freeze and assume helplessness, offer supportive questions NOT answers.

- Ask “What do you do next?”

- and “Then what do you do after that?”

- and so on.

You will be surprised by how quickly and enthusiastically students will begin to try and fill in the answers. What you are doing here is encouraging students to take over the job for themselves. They sometimes need reminding that uncertainty shouldn’t lead to paralysis!

- Ask ‘you questions’ to help students identify with the subject matter.

- What do you know about this?

- What do you want to know?

- Have you ever been to…?

- Have you ever heard of…?

- What do you think is feels/felt like…?

By demonstrating a piece of tricky learning you could show students how you personally find learning difficult, and model the strategies you use to overcome such difficulties. The idea is that sharing these experiences encourages students to imitate ways of overcoming difficulty.

Give yourself a challenge

First ask yourself…

- Am I aware of my students’ negative perceptions of learning?

- Which negative perception of learning would I say was the most prevalent?

- Do I reckon I could switch this around?

- What sort of tactic might I try?

And when you do make a breakthrough…

- make a note of what worked with whom and share the idea with colleagues.

We hope you enjoy using some of these ideas in your classrooms. Let us know here or on our Facebook page how you get on – or to share ideas of your own!

Contact us, to discover how together we can help your students become better learners.

No comments yet.